In early 2021, our peach trees in Catalonia were in full bloom. I was looking forward to a rich harvest. But then frosts came back. They killed off the fragile blossoms and with them the coming harvest. On a visit to La Junquera, a farm in Southern Spain, I learnt that the same happened to them, but on a much larger scale. Yanniek Schoonhoven and Alfonso Chico de Guzmán, who run La Junquera, lost almost their entire peach crop that year.

I visited them for my book Feldversuch. And after doing years of research on agriculture for the book, I realised something that I think is under-appreciated. The problem about climate change is not so much rising average temperatures, it is the change itself, the uneven distribution and the unpredictability that comes with it.

Take wheat for example, under ideal conditions it grows under temperatures from around 15 to 23 degrees celsius from seed to harvest. If you have a temperature increase of 1,5 degrees celsius that was evenly spread, you could simply seed and harvest a little earlier (ignoring hours of sunlight here). But this is not the case. Increases are locally concentrated, leading to temperatures that make growing there almost impossible. And there are wild swings. Southern Germany saw record breaking early April temperatures of 30 degrees celsius two days ago. Next week temperatures are forecast to drop to around nine degrees in the same regions with night frosts likely.

Crops also need a good amount of rain during the growth period. For wheat, and many other plants, the average yearly amount of rain is less important than the amount of rainfall during the growth period. You can have a bad harvest, even if the average rainfall hasn’t changed one drop.

A NASA study suggest, that climate change will affect global crop yields within the next ten years. Corn is expected to drop globally by 24 percent, while wheat yields could increase by 17 percent. While this is already a massive shift, I have doubts that the increase in expected wheat yields is realistic. While total wheat production has increased in recent decades, it has dropped from 2022/23 to 2023/24. Stockpiles of grains have dropped to a 16-year-low according to Reuters.

My hypotheses is that many predictions on future harvests fail to address the unpredictability-element in the equation and predictions are overly optimistic. Let us look at something that backs up my guess: harvests that were already brought in (or not brought in) in 2023.

Africa

In the Ivory Coast, cocoa production is expected to drop by 20 percent compared to recent years. The trend can bee seen in much of West Africa. Global cocoa prices quadrupled in 2024 compared to recent years.

North America

South America

Europe

Asia

In China’s Henan province, the country’s bread basket, heavy rain battered wheat fields and impacted much of the harvest. Later that year, heatwave threatened China’s autumn crop, which led the authorities to issue emergency alerts.

Australia

Some of these events are because of localised extremes (Spain, Australia), others because of extreme swings (Georgia) and yet others because of weather disasters (Florida).

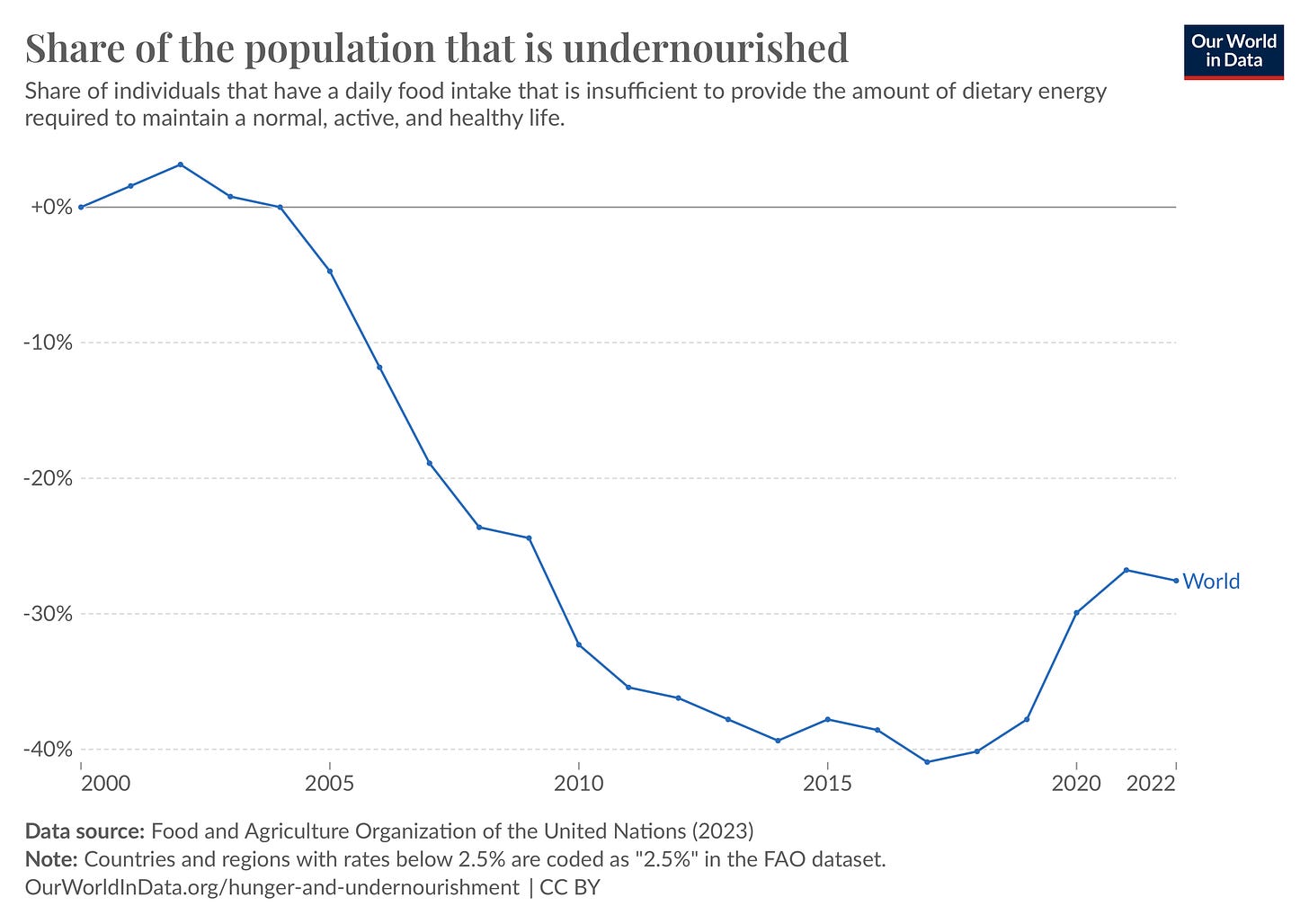

While this is only anecdotal, there are more indicator of a looming food crisis: the amount of people being hungry. In 2019 there were 678 million people affected by hunger, in 2021 it was 828 million.

This mirrors what people from the World Food Program told me. Until about 2015, all indicators were improving, then they plateaued and since 2019, we are seeing a large increase in the number of hungry. This can partly be explained by the war against Ukraine and Covid, but is undoubtedly due to climate change as well. One of the worst affected regions is the Horn of Africa, where several subsequent rainy seasons remained dry.

The food crisis is already there for millions of people. Let’s be clear, this is not because of a lack of food produced globally, it is still more than enough. It is because of uneven distribution and mostly affects already disadvantaged people. In Europe and the US, the only effect so far is rising prices of tomatoes and olive oil. But we should not bet that this will not affect us in more serious ways. And we should prepare by making our food systems more resilient towards extremes and extreme swings. (I write about ways to do that in Feldversuch.) And we should be prepared for potential losses. Some countries are already doing that. Norway has recently started stockpiling wheat.

Hi! Checkout my new free substack community where we are gathering answers about geoengineering! Let's band together!

https://trackthetrails.substack.com/p/track-the-trails